Darwin Tree of Life in 2021: Tireless fieldwork and the first beautiful genomes

Having overcome a challenging 2020, with plans put back by a global pandemic, the Darwin Tree of Life project has flourished in 2021. Teams have been collecting species across these islands, from the mountains of Scotland, to the sea caves of Wales, and the forests of Oxfordshire. Back in the labs we’ve been processing protists, extracting DNA, and assembling and publishing the first of our high-quality, reference genomes.

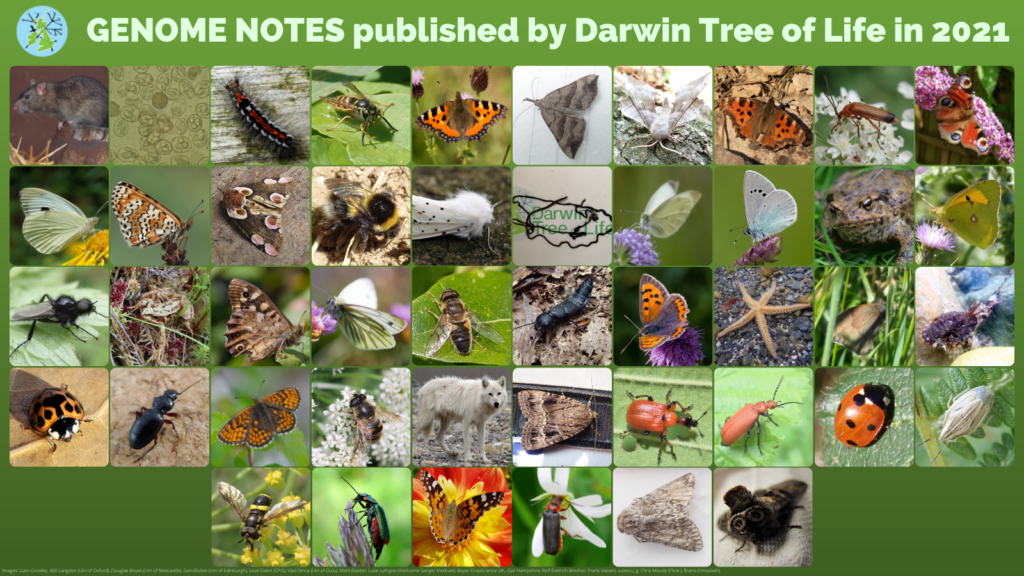

With 2022 on the horizon, we have assembled over 200 genomes and published almost 50 of those as Genome Notes – insects, amphibians, fish, echinoderms, one very long worm, and even a wolf. And we’re just starting to ramp up!

Intensive fieldwork, on land and sea

Natural History Museum, London

This year saw some intensive fieldwork, on land and sea, which kept the NHM DToL team very busy. Fieldwork took place in South-East England and Scotland along with NHM curators, NatureScot, Sanger and a network of experienced entomologists.

In 2021 NHM has collected around 1,700 specimens of 1,100 species. Highlights were trips to Beinn Eighe NNR in the far NW of Scotland, marine sampling at Millport, and summer days in SE England chalk grassland. The sampling team joined a Dipterists’ Forum trip to Cornwall in August, resulting in a flood of flies for DToL.

Keen folk at NHM provided a steady flow of new centipedes, millipedes, moths, beetles and wasps for the project. Along with the common and the rare, numerous invasive or newly arrived species have also been sampled, so we have a good snapshot of the ever-changing UK fauna.

NHM also had their first Genome Note published, of the St. Mark’s fly (Bibio marci), our first species to go full circle from collection to a whole genome freely accessible to the general public. New recruits at NHM are Inez Januszczak as sampling coordinator and Dominic Phillips as research assistant maternity cover.

An ecological ascent of Ben Nevis

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) spent a total of 63 days in the field from May to October, with sampling events primarily concentrated on the species priority list, focusing on family representatives or target species. An RBGE led expedition to Ben Nevis resulted in the collection of the ecologically important snowbed species Polytrichastrum sexangulare, the Northern Haircap, only ever found near the summits of our highest mountains where small patches of snow persist nearly all year round.

Further sampling highlights include: Eriocaulon aquaticum, the pipewort, restricted to a few sites on the Scottish Isles, collected from Skye; Scheuchzeria palustris, aptly named the Rannoch Rush as it only occurs on or close to Rannoch Moor; and Diapensia lapponica, the pincushion plant, found on only one mountain top at Glenfinnan in the Highlands. Each of these three species are the only representative of their family found in the UK.

Overall, in the main collecting season from May to October, the RBGE Genome Acquisition Laboratory (GAL) collected 2,091 DToL samples, representing 143 species of vascular plants, 84 bryophytes, and 3 lichens. An additional 149 samples, representing 25 plant species, have come through the RBGE GAL in collaboration with Buxton Climate Change Impacts lab. Ultimately, 1,716 samples were shipped to the Sanger Institute, including 144 bryophyte samples for the plant R&D panel and 333 samples for the Apple Day project. In total, RBGE has sampled 398 plant species to November 2021 (185 bryophyte species from 79 families, and 204 vascular plant species from 87 families).

Shock sighting of a silver fly – the first in Wytham Woods

University of Oxford, Wytham Woods

After a couple of years intensively sampling Wytham Woods, the team were not expecting to find many more species that were ‘new for the site’ this year – how wrong they were! In fact, 2021 proved to be a bumper year for rare and interesting species. And one discovery stood out from the rest.

On July 8th the team were undertaking a day of intensive sampling in an area of the woods known as ‘the Dell’. They were mainly targeting beetles that live in dead wood as there were several families in this group that were yet to be collected. Liam Crowley spent some time examining a particularly huge veteran beech which had fallen over, revelling in the diversity of saproxylic insects it hosted.

Whilst Liam was admiring the abundance of solitary wasps buzzing in and out of their nest holes in the tree, a large fly flew over his shoulder and landed on the trunk right in front of him. ‘Therevid!’ he thought, great, they hadn’t collected that family yet!

As Liam moved nearer, net in hand, and got a closer look, he nearly fell over with shock. The fly was bright silver! The common woodland species in this family are all brown. Silver species are usually only found on coastal dunes or are vanishingly rare.

Sure enough, he was able to confirm this specimen as Pandivirilia melaleuca, the forest silver-stiletto fly. This species is very scarcely seen and was previously only known from Windsor and the surrounding area, and a second cluster in West Gloucestershire and South Worcestershire. Wytham Woods falls neatly in between these two groupings. Not much is known about the biology of this species, but the larvae are believed to develop in the heartwood of dead trees where they prey on saproxylic beetles. This specimen represents the first species from the family Therevidae submitted for full genome sequencing.

Journey to a seldom-studied protist paradise

University of Oxford, Protist Group

Priest Pot is a body of freshwater, about one hectare in surface area, near the village of Hawkshead in the Lake District. The site, part of a National Nature Reserve, appears fairly unremarkable. However, these waters are teeming with a huge variety of single-celled organisms – known as protists – blooming and feeding in their own complex ecosystem beneath the surface.

The DToL team scouted out this seldom-studied protist paradise in 2020, finding the site surrounded by swampy undergrowth and a fence wrapped in barbed wire. Getting in touch with the landowner also took persistence. When Estelle Kilias’s emails went unanswered, she even tried sending a letter. An email response soon followed, and progressed to many friendly phone calls.

It was September 2021 by the time the Oxford University team were out on Priest Pot’s waters. “You feel every bone,” Estelle recalls of the fieldwork. First they lowered probes to find the most interesting environmental conditions in the lake – these determine whether rarer protists will be thriving. Next they plunged in five-litre Niskin bottles to precisely select the water they needed, pouring them into 20-litre carboys and taking them back to shore. Ultimately, a hundred litres of sample water were collected and taken back to the lab in Oxford, where their protist treasurers are being painstakingly discovered.

Seeking genomes beneath the surface

Marine Biological Association

It’s been a busy year of collecting and processing for the Marine Biological Association DToL team, with 568 different species collected from 351 different families and 188 different orders. That includes marine lichen, fungi, algae, fish, crabs and more. Although there have been quite a few field-working trips, a huge amount of these species have been collected right on the MBA’s doorstep in Plymouth.

Britain and Ireland has the most incredible diversity of marine life (this is, after all, an archipelago) but a lot of it is hidden to most of the people who live here. Team MBA has set out to uncover what lives beneath the waves: they have been out on boats, diving through marinas, wading through rockpools, clambering over muddy tidal flats and scrambling into watery caves to find all sorts of creatures living in all sorts of strange places.

Below is a selection of some of the amazing marine life they found this year.

1. The parchment worm (Chaetopterus variopedatus) is a bioluminescent polychaete worm that builds itself a papery tube from secreted mucus – as seen top right in this photo.

2. Lichens are a stable symbiotic relationship between algae or cyanobacteria and fungi. So little is known about lichens, that DToL teamed up with other MBA colleagues working on lichens to help us find and ID these tricky species. Lichen are tiny ecosystems and cleaning them up to prepare them for DNA barcoding was a long and arduous task, but MBA’s in-house barcoder Joanna Harley did a marvelous job, getting good reads for many of these notoriously difficult organisms. Here is the black lichen Lichina pygmaea.

3. This is a sea spider, Pycnogonum litorale, one of 1,300 species world-wide. The scientific order they belong to is called Pantapoda, meaning ‘all feet’, very appropriate for these leggy animals.

4. This beauty is a worm pipefish (Nerophis lumbriciformis). These animals live mostly in and around rockpools, like other pipefish and seahorses the males carry the young, and they mate for life, so if you see one make sure to leave it be!

From big data to beautiful genomes

Wellcome Sanger Institute’s Tree of Life programme

To date, well over 200 DToL genomes have been assembled and curated by the dedicated teams of bioinformaticians at Sanger – the vast majority of them in 2021.

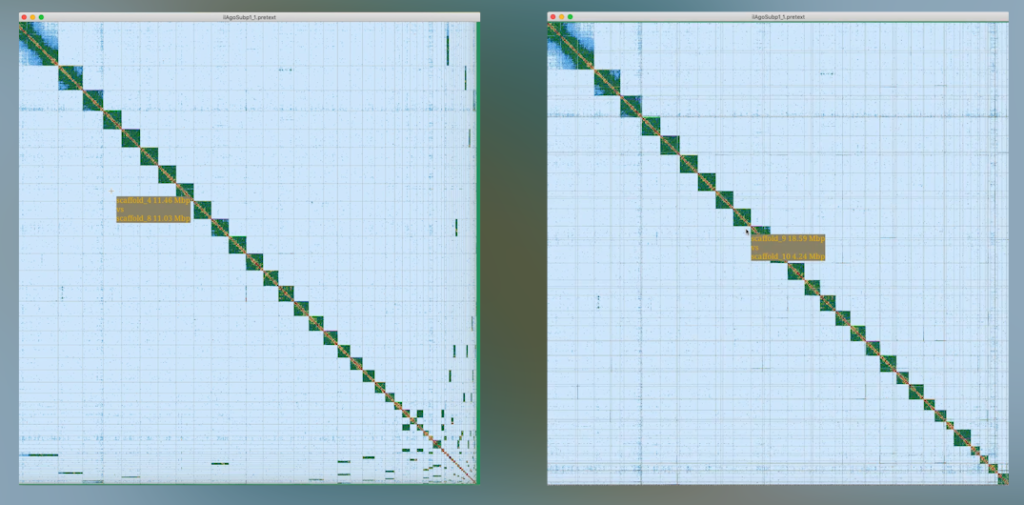

The Tree of Life Assembly (ToLA) team and Genome Reference Informatics Team (GRIT) are responsible for turning masses of DNA data – those A, C, G and T base pairs – into beautifully assembled and curated genomes. Crucially, these are arranged in chromosomes, to reflect biological reality as closely as possible, before being released to the scientific community.

“We have received triple the number of curation requests compared to 2020,” explains Jo Wood, who heads GRIT. “As we do this, to meet the ambitious goals of the project, we are constantly looking for ways to increase throughput and improve turnaround whilst maintaining quality. A huge amount of effort has gone into streamlining, automating, and generally reducing the human hands-on time required.”

The two teams work closely together to make sure the final genomes are of the highest possible quality. For example, this year GRIT spotted some missing data when curating an apple genome. The ToLA team then investigated and uncovered a couple of bugs in the programs.

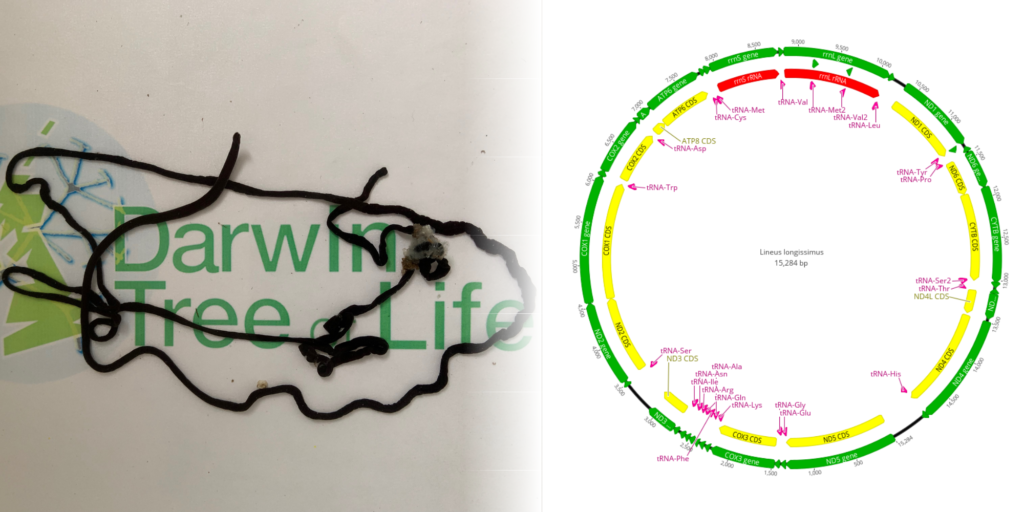

“Our pipeline is working on a huge variety of different organisms, such as plants, worms and lepidoptera,” says Marcela Uliano-Silva, a senior bioinformatician on the ToLA team who has this year also written a tool for assembling mitochondrial DNA from Pacbio HiFi reads. “To put into perspective how far the science has come: two decades ago the human genome was published, having taken 13 years, almost $3 billion and nearly 3,000 scientists. We’re now producing several new genomes per week, in much higher quality and at the chromosomal level.”

One of the genomes the Sanger team worked on was that of the super-stretchy ribbon worm, Lineus longissimus – which, at full length, is the longest animal in these islands. Its genome, however, was just an eighth the length of the human genome. Compare that to the mistletoe genome which is 30 times larger than the human genome – and is one of the trickier genomes the project expects to sequence and publish in 2022.

Open access data, phylogeny and Our Animal DNA

EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI)

This year has been all about butterflies and moths for the DToL team at EMBL-EBI. The Ensembl Compara team generated a cactus alignment – a method for creating multiple genome alignments – of around 90 butterfly and moth (lepidoptera) species along with several closely related species.

Open access to the annotated genome assemblies created will enable more detailed exploration of the evolution of the genome structure within the lepidoptera. These genomes are freely available to anyone through Ensembl Genomes and the DToL data portal.

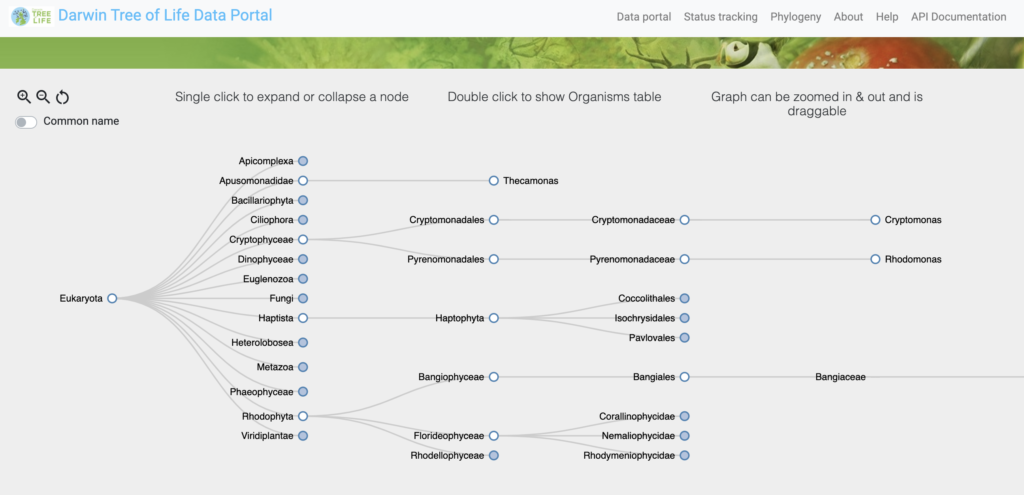

The EMBL-EBI team also updated the DToL Data Portal to include a phylogeny browser that allows users to navigate a tree-like structure and see what data is available for a particular clade, family or genus.

And in public engagement news, EMBL-EBI now offers a unique DToL public engagement activity, Our Animal DNA, developed by Ensembl Outreach. This activity is available for school students aged 16–18 years and will introduce them to bioinformatics tools and techniques through an introductory video from our scientists, and online classroom activities.

Barcoding the Broads

Earlham Institute

In September, the Earlham Institute launched the first in-person training workshops for its Darwin Tree of Life public engagement programme: Barcoding the Broads. The sessions are tailored for a non-specialist audience and focus on a technique called DNA barcoding, where an organism can be identified by analysing unique patterns of DNA within its genome.

The methods are straightforward and reliable thanks to huge advances in sequencing technology and the miniaturisation of lab equipment, meaning anyone can identify an organism with a little bit of training and support.

The team at the Earlham Institute, led by Sam Rowe, have had some fantastic initial feedback from teachers, naturalists, sixth form students and education professionals who attended the first few sessions. Plans are also in place for future work to help communities in Norfolk explore the biodiversity on their doorstep.

By the end of 2021, training would have been provided to 50 people with almost 100 more booked in for, or hoping to attend, a workshop at the start of 2022. In partnership with Kew Gardens, the team has also been successful in an application to the Enabling Connections Fund, which allows them to embark on an exciting new collaboration with the Norfolk Fungus Study Group to explore DNA barcoding with fungi on the Norfolk Broads.

DNA barcoding workshops run from 9:30am-4:00pm on the Norwich Research Park and are free to attend for groups of up to nine people. If you would like to get involved to learn new techniques for your research and/or education work then please visit the Earlham Institute website and get in touch with the team.