School Fly Trap: Students find world's smallest wasp in their playground

In the last week of the summer term, under a blazing blue sky, thirty excited children gathered round a tent-like contraption in a corner of their school grounds. This structure was called a Malaise Trap. The children had set it up, with the help of Darwin Tree of Life scientists, to study flying insects.

After two days of waiting, they opened the trap to find they’d collected over 300 specimens from at least 100 different species. Cue wide eyes, big smiles, and more wow’s than you can shake a microscope at.

The School Fly Trap Project

The Year 5 class at R A Butler Academy were pioneers for the latest Darwin Tree of Life public engagement programme. Titled the School Fly Trap Project, the activity will visit five primary schools in Cambridgeshire and Essex over the next school year.

Mara Lawniczak leads the engagement team alongside her research, and describes how the scientists are aiming to give “a sense of the impressive biodiversity of insects right on school grounds” and “how DNA can help us study that biodiversity… and how it can change biology”.

Scientists visited the school, located in Saffron Walden near the Wellcome Genome Campus, twice over the course of a three day period. Day one laid the groundwork, with talks and games about insect body parts and DNA codes, led by moth-genome researcher Charlotte Wright and group leader Mara.

The pupils then selected a site in the playground to set up their malaise trap, where it could stay undisturbed until the scientists returned in two days’ time.

Caught in a trap

Malaise traps, like the one the students set up, are used by scientists around the world to sample flying insects such as moths, bees and hoverflies. The trap consists of a tent with open sides, a vertical pane of fabric mesh in the centre, and a sloping white fabric roof above. Insects flying through the tent collide with the mesh, instinctively fly up into the white roof, and follow the sloping fabric as it funnels them upwards.

At the top of the roof is a bottle filled with a preservative chemical. Insects caught in the trap fall into this bottle and are collected for later study.

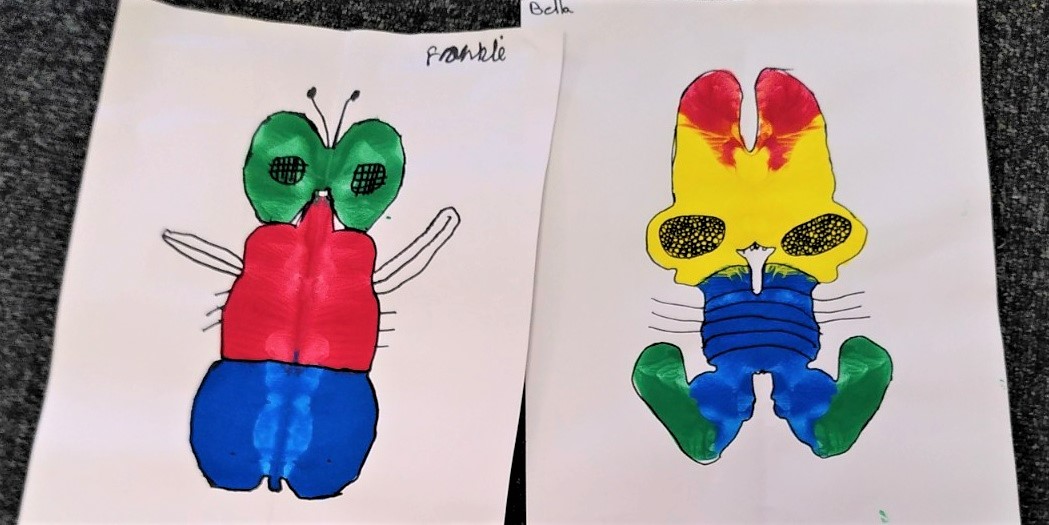

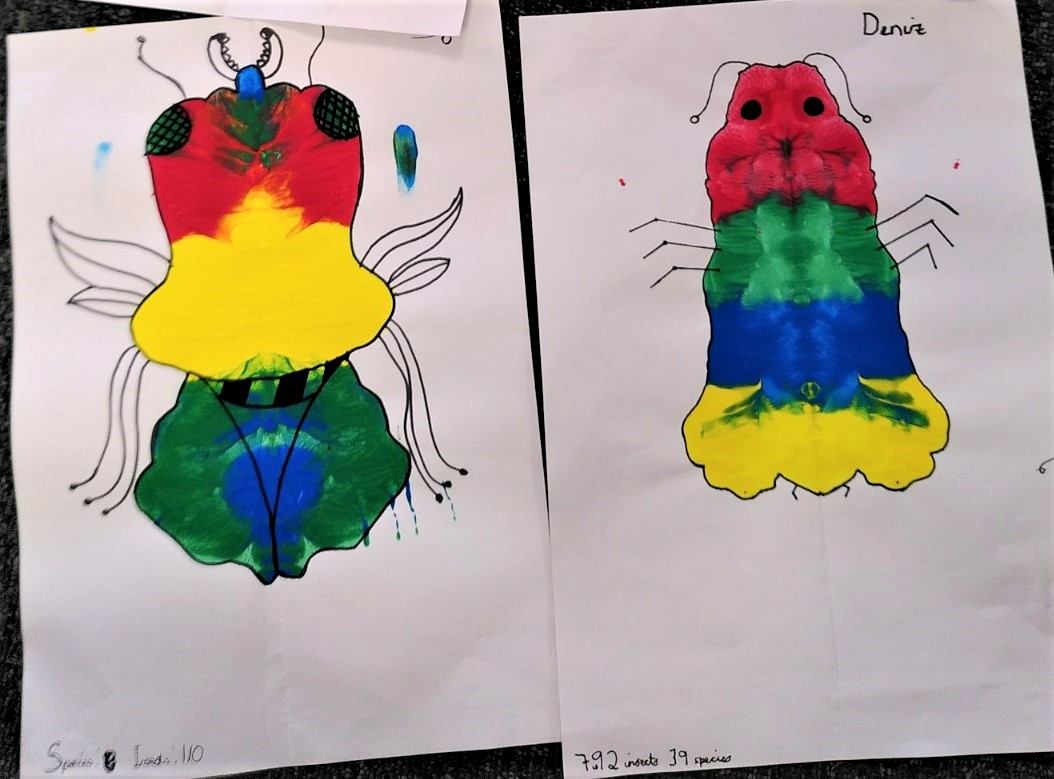

Our scientist’s second visit began with an art activity – using the insect body parts the children had learned about in the previous session to decorate paint-blots (see top image and below). The result was a wide diversity of lifeforms, created using the same four colours representing the simple DNA ingredients: A, C, G and T.

The students then predicted the numbers of insects and species they would find when they opened the trap. Their guesstimates were low – usually in the forties or fifties. So the class were in for a surprise when, still carrying their insect paint prints, they opened the trap and saw the real-life insect menagerie revealing the full diversity of their playground.

The children were head-bobbingly excited to see the huge amounts of different insects collected. There were several hundred specimens to identify, from big to small, colourful to monochrome. The collected insects were shared out amongst the class and students examined them with the aid of hand lenses and microscopes.

“Smaller than a grain of sand”

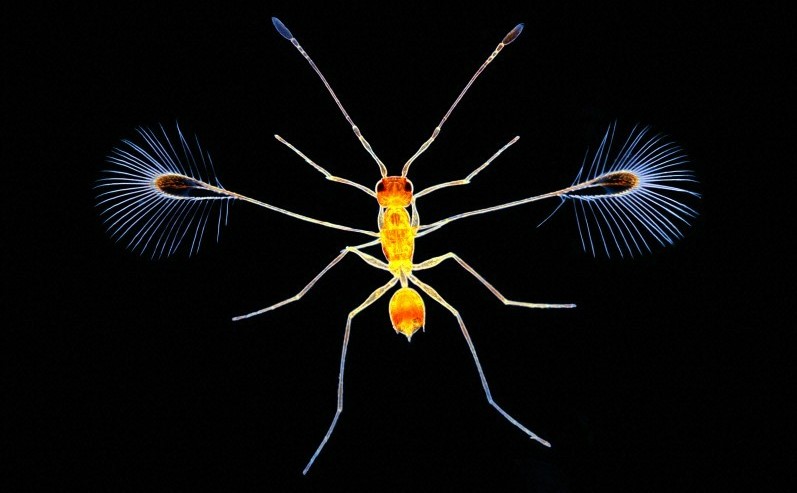

Each student chose an insect to write about in detail, and to sketch for their observation record. When sharing these with the class one student said that they’d found an insect “smaller than a grain of sand”.

Our insect expert Lyndall Pereira quickly identified this tiny lifeform as a member of the fairy wasp family (Mymaridae) – this family of miniature parasitic wasps contains the smallest wasp (and the smallest flying insect) in the world. The children’s insect was too small to identify to a species level with the available equipment, but this is where the next stage of the research project can step in – DNA barcoding.

After examining with a hand lens, students used forceps to select individual insects and place them into wells. Now ready to have their DNA extracted and sequenced at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the insects’ identities would be revealed by their unique DNA codes.

Like a barcode on an item of shopping, DNA regions that are specific to particular species are called DNA barcodes. These regions allow scientists to identify with a high degree of certainty what species they have collected even if these specimens are too tiny to tell with a microscope.

The insect samples that School Fly Trap students collect will be DNA barcoded to give an accurate snapshot of the flying insects that visit the school playground. Scientists can then use these snapshots to build up a picture of how insect diversity varies across the local area. With all sorts of different insects required to support a healthy and diverse ecosystem, a better understanding of where species are, and where they are not. This will be a huge asset to conservation efforts.

The students finished the session by making their own DNA barcode bracelet, matching the real DNA codes of some of the insects collected during the study.

Our scientists will be returning to R A Butler Academy next term for more insect collections, as well as to four more schools in the surrounding area. Look out for future blogs about the School Fly Trap Project, and our next insect collections, in October 2021.

Jack Monaghan is Public Engagement Coordinator at the Darwin Tree of Life project.