Snail hunting in the dark sea caves of Wales

It has been a busy few months of collecting for the Darwin Tree of Life team based at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth. With the lifting of COVID restrictions, everyone was back out in the field collecting all kinds of marine wonders for genome sequencing.

Because the project is so varied, and we are looking at so many different types of living things, we often work closely with experts who can identify tricky groups that can take a lifetime of study to tell apart. To this end the DToL team headed off to Pembrokeshire to join the Conchological Society of Great Britain & Ireland on their yearly snail hunting trip.

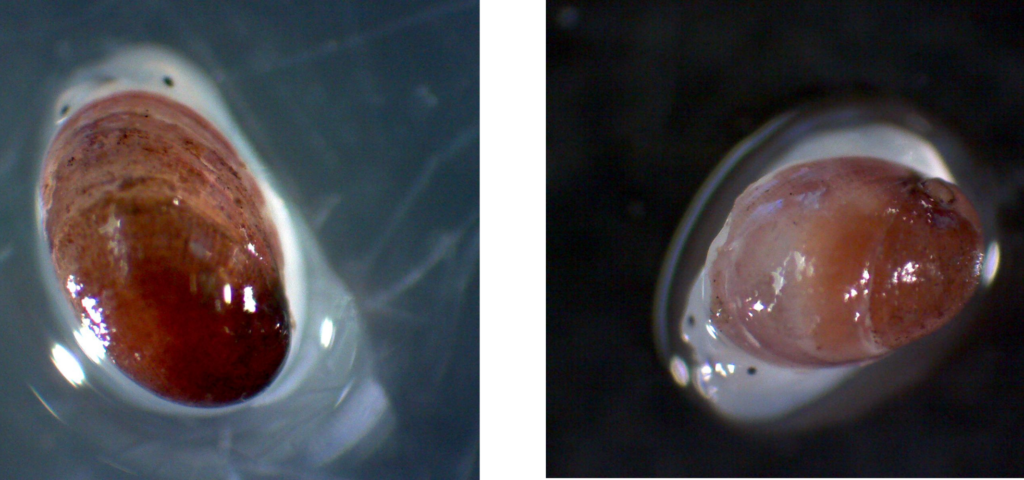

Our first day found us wading through deep pools and into some dark caves, with Conch Soc member Bas Payne. We were searching the walls for a tiny marine cave snail called Otina ovata, which tend to live above the line of barnacles and other invertebrates, on the smoother walls. Otina ovata at first glance look like tiny limpets, but they have a lot less suction, coming off the walls easily. They’re so small you would easily miss them, but luckily we had Bas on our side and managed to collect a group of these teeny snails.

The snails then had a long journey back to our labs in Plymouth, but with the help of some cold packs and wet tissue paper they all made it.

Once under the microscope the characters of these tiny gastropods really came through, they were so zippy it was hard to get a good picture, they seemed determined to explore every inch of the petri dish. We have found this is often the case with the smallest of animals, they might go completely un-noticed outside in their environment, but as soon as you look at them on their own scale they come alive in a totally different way.

Many of the creatures we find don’t have common names yet, as they are too small or haven’t had enough public interest. We think this is a bit of a shame, so have been adding in common names whenever we can. In future, when people look up Otina ovata, they will be able to see that they are also called Bas’s cave snail, in honour of our hardworking snail expert who led us fearlessly into sea caves to find these, and many other gastropods for our project.

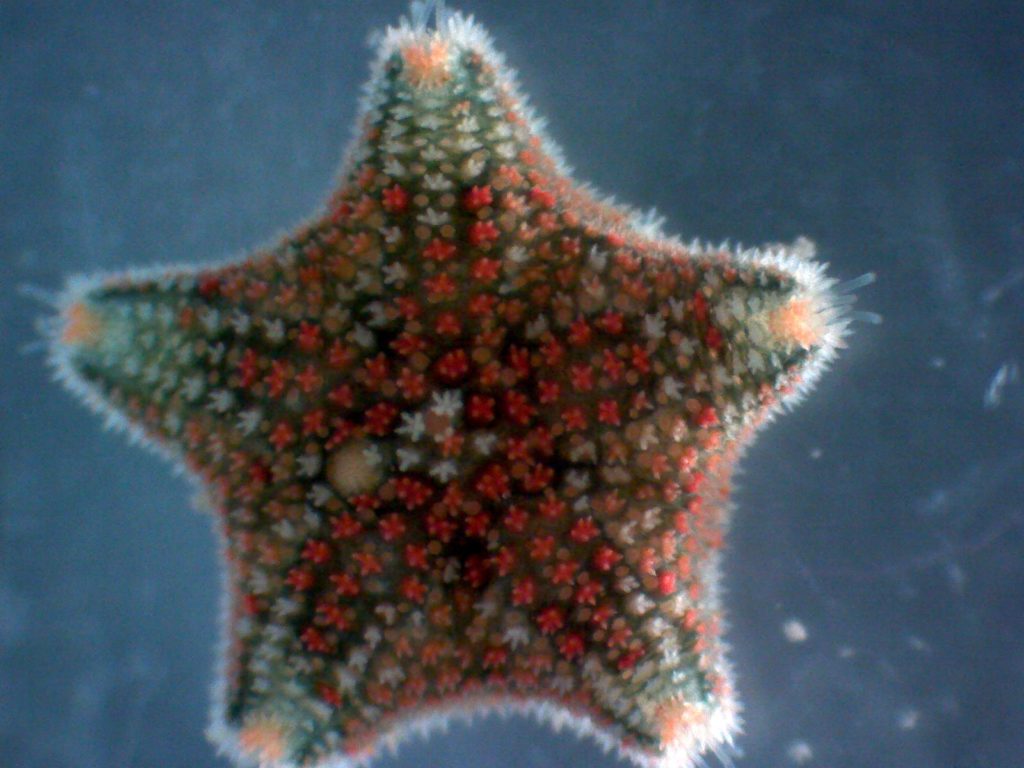

While on our Pembrokeshire visit, the DToL team took some time out from snail hunting to find another mysterious animal. Asterina phylactica is a small cushion star that we had heard tales of being found in a specific group of rockpools near FSC Dale Fort, the marine centre that hosts many marine biologists (including us).

After connecting with marine specialists Anne and Francis Bunker, we were directed to some hidden rock pools, filled with small cushion stars. There is currently a study going on in these rock pools, so Anne and Francis helped us to seek out where there were individuals which we could take without interrupting the experiment. These tiny sea stars are covered with a surface of tiny orange star shapes, a star within a star within a star, so we named it the recursive cushion star, for its repeating pattern.

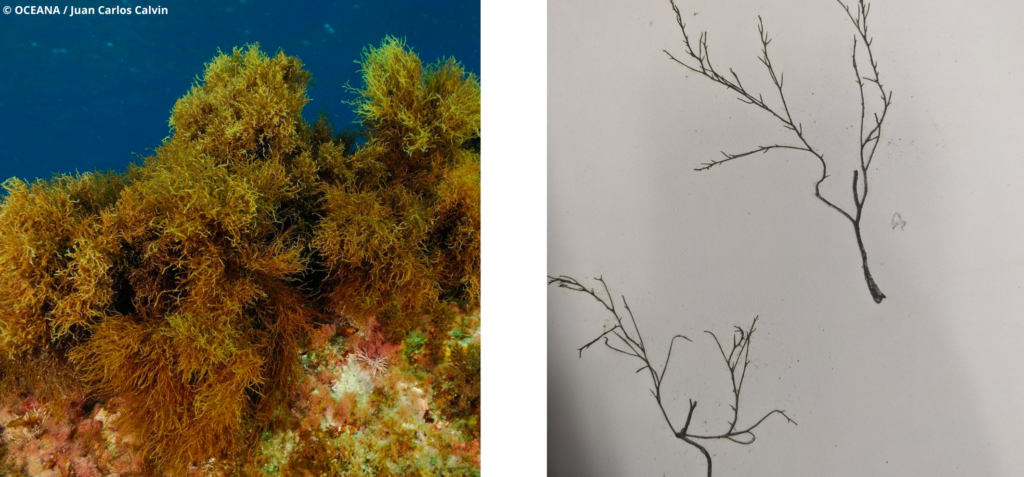

Anne and Francis also led us to some particularly beautiful seaweed, a species called Cystoseira nodicaulis or bushy noduled wrack, which has a lovely blue iridescence, although at this time of year it wasn’t looking quite its best self.

This species has changed scientific name a number of times, and is an example of how common names can be useful to track down information. Although common names can sometimes be used for several species, they can also sometimes be used to clear up confusion on a species that has been re-named a lot – and can sometimes be quite descriptive of the species, or just a lot of fun!

Transporting the tiny snails and other organisms is no mean feat, some of them are used to fluctuating temperatures and oxygen, but for others they live in such specific places that they aren’t used to constant changes and keeping the temperature and oxygen at the right level for such a tiny thing while on the road is not easy. Luckily most of our animals made it back alive, and we managed to process samples for 17 different species.

However, some of these snails were so small that we will have to wait for a little technological advancement so that we can actually get enough DNA for a read. The DToL project is pushing the science forward in leaps and bounds in that regard, and we don’t think it will be long until we have a completed sequence for these, and all the other tiny marine animals we find on our collection journey.

That’s when the science gets even more exciting. With DToL’s data open and free for anyone to use, researchers across the globe will be able to use genomics to better understand and protect these creatures. But in the meantime they are safely stored on ice.

This article was written by Kesella Scott-Somme, research assistant at the Marine Biological Association.