Halloween genomes: 5 spooky species newly sequenced

Certain species have fuelled human fears and superstitions in Britain and Ireland for centuries. But just because some Homo sapiens have decided these organisms are in league with the devil doesn’t mean they aren’t an integral and fascinating part of the ecosystems upon which we all rely.

To mark Halloween, Darwin Tree of Life sets out to clear the name of five of these much-maligned species. All have either been released as Genome Notes recently or will be in the near future: watch this space.

Bufo bufo, more than an ingredient in a witches broth

Unlike its relative the frog, hopping into fairytales as a potential princely love match, the common toad has become synonymous with witchcraft: whether as a witch’s familiar or a key cauldron ingredient. This amphibian divide isn’t so obvious at the genomic and evolutionary level, as we discovered in a previous article about the surprising differences (and similarities) between frogs and toads.

For Britain’s toads themselves, modern horror comes in the form of a chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, causing a disease which can wipe out entire local populations. One use for a high-quality genome for B. bufo is to better understand how more resilient populations are surviving the fungus and to help conservationists plan strategies for protecting this imperilled amphibian.

Read the Bufo bufo Genome Note here.

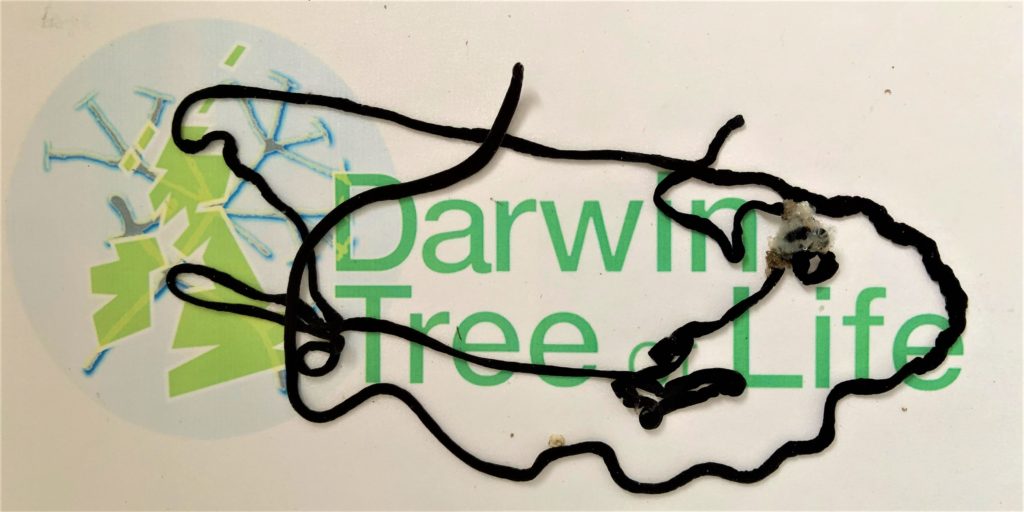

Lineus longissimus, a marine worm with toxic mucus

Some might argue this Nemertean ribbon worm is as close as these isles get to a bona fide sea monster. With specimens known to stretch to 55 metres in length, this species is claimed as the longest animal – a disputed claim because it relies on the fact that Nemerteans are incredibly elastic. L. longissimus is also very slimy, and can deploy toxic mucus to paralyse prey such as crabs. In 1555, a Swedish archbishop and naturalist explained: “The worm is entirely harmless, unless touched by a human hand. In that case, the fingers will swell when the animal comes into contact with the skin of the hand.”

But this species may also be the key to new chemical compounds for use in industry, agriculture or medicine. Its toxins were only extracted and fully described in 2018. Marine organisms have provided thousands of chemicals with many uses to humanity – who knows what further studies of Nemertean genomics might reveal?

Read the Lineus longissimus Genome Note here.

Canis lupus, the wolf at the door

Darwin Tree of Life will soon be publishing a Genome Note for the Greenland wolf, Canis lupus orion, one of the many subspecies of the grey wolf. Perhaps no other mammal provokes as much fear in the historic human psyche. From Bible quotes and folklore fables to werewolf legends and modern movies, the wolf is repeatedly cast as the villain. In truth, when Canis lupus encounters Homo sapiens it usually only goes one way: wolves were eradicated from Britain around 300 years ago, leaving a predator-shaped hole that has unbalanced our ecosystem ever since.

However, many of us have chosen to live alongside wolves. The domesticated dog diverged from Eurasian wolves (Canis lupus lupus) around 33,000 years ago. Our newly sequenced Greenland wolf genome is especially interesting to those studying the wolf-dog link. Because it is a North American subspecies separated from Eurasian wolves, and also one that is not closely related to coyotes, the Greenland wolf should prove the perfect reference genome for researching the differences between dogs and their Eurasian wolf ancestors.

Read the Canis lupus Genome Note here.

Sacculina carcini, the parasitic barnacle that castrates crabs

If you think barnacles don’t belong in a list of horror tropes, you’ve clearly never pondered the life cycle of Sacculina carcini. Known as the ‘crab hacker barnacle’, these parasites infect green shore crabs (Carcinus maenas). Stricken crustaceans can be recognised by a reddish coloration spreading throughout their body and a structure under the abdomen resembling a crab egg mass. This mass is in fact the female S. carcini. Having infected its host, the barnacle castrates the crab and takes control of the body, redirecting nutrients from the unfortunate crustacean in order to produce its parasitic larvae. Male larvae live as parasites on the female, fertilising her eggs before they are released into the environment to infect new hosts.

The genome sequence for S. carcini will shed light on how this group evolved such a distinct appearance and lifecycle from other barnacles (Charles Darwin famously didn’t spot any relationship). It will also help marine fisheries tackle this problem parasite, which hinders the reproduction and growth of crabs.

Ocypus olens, not the beetle from Hell

The devil’s coach horse has been associated with evil and the devil in folklore since the middle ages. This large all-black rove beetle certainly exhibits some striking behaviour: when agitated, it rears its abdomen and opens its mandibles in a threat-posture. The devil’s coach horse is also capable of inflicting a painful bite to any human foolish enough to handle it, and readily produces defensive secretions from the mouth and tip of the abdomen.

But far from being a denizen of Hell, O. olens is a very successful species and a key part of the ecosystem across most of Europe and North Africa. It is a generalist predator, feeding on many different invertebrates as well as carrion. And while it is not an immortal hellspawn, the adults are relatively long-lived for a beetle, existing in this final life stage for up to two years.

Read the Ocypus olens Genome Note here.